Causes of meningitis

Viral meningitis

Most cases of meningitis are caused by viral infections. A wide variety of different viruses can infect the central nervous system. Most viruses are capable of causing either meningitis or encephalitis, although, in general, a given virus is more likely to cause one syndrome rather than the other. A number of viruses produce aseptic meningitis including enteroviruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), West Nile virus (WNV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), mumps, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCM)

Enteroviruses — Aseptic meningitis occurring during the summer or fall is most likely to be caused by enteroviruses (eg, Coxsackievirus, echovirus, other non-poliovirus enteroviruses), the most common causes of viral meningitis. However, seasonal variation of certain CNS viral infections is relative and not absolute. Enteroviruses continue to cause 6 to 10 percent of cases of viral meningitis in the winter and spring despite their predilection for inciting illness in the late summer and fall.

HIV infection — Primary infection with HIV frequently presents as a mononucleosis-like syndrome manifested by fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, rash, and pharyngitis. A subset of these patients will develop meningitis or meningoencephalitis, manifested by headache, confusion, seizures or cranial nerve palsies.

Herpes simplex meningitis — Primary HSV has been increasingly recognized as a cause of viral meningitis in adults. In contrast to HSV encephalitis, which is almost exclusively due to HSV-1, viral meningitis in immunocompetent adults is generally caused by HSV-2. Between 13 and 36 percent of patients presenting with primary genital herpes have clinical findings consistent with meningeal involvement, including headache, photophobia and meningismus. On the other hand, genital lesions are present in approximately 85 percent of patients with primary HSV-2 meningitis and generally precede the onset of CNS symptoms by approximately seven days.

Recurrent (Mollaret's) meningitis — Mollaret's meningitis is a form of recurrent benign lymphocytic meningitis (RBLM), an uncommon illness characterized by greater than three episodes of fever and meningismus lasting two to five days, followed by spontaneous resolution. There is a large patient-to-patient variation in the time course to recurrence that can vary from weeks to years. One-half of patients can also exhibit transient neurological manifestations, including seizures, hallucinations, diplopia, cranial nerve palsies, or altered consciousness. The most common etiologic agent in Mollaret's meningitis is HSV-2, although some patients do not have evidence of genital lesions at the time of presentation.

Noninfectious etiologies for Mollaret's meningitis have also been proposed. As an example, patients with an intracranial epidermoid cyst or other cystic abnormalities in the brain can develop meningeal irritation due to intermittent leakage of irritating squamous material into the CSF.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus — Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a human zoonosis caused by a rodent-borne arenavirus. LCMV is excreted in the urine and feces of rodents, including mice, rats, and hamsters, and is transmitted to humans by exposure to secretions or excretions (by direct contact or aerosol) of infected animals or contaminated environmental surfaces.

Mumps — Aseptic meningitis is the most frequent extrasalivary complication of mumps virus infection. Prior to the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967, this paramyxovirus was a relatively common cause of viral meningitis, accounting for between 10 and 20 percent of all cases.

Miscellaneous viruses — A number of other viruses can infrequently be associated with viral meningitis. In certain areas of the United States, arthropod-borne viruses can cause aseptic meningitis. West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and California encephalitis group of viruses all can cause aseptic meningitis but more frequently are associated with encephalitis. Other causes include varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human herpes virus-6, and Zika virus

Bacterial meningitis

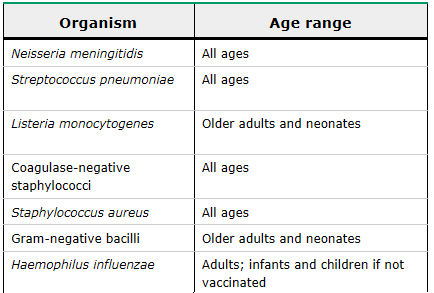

The frequency of the different etiologic organisms of bacterial meningitis varies with age. Bacterial meningitis can be community acquired or healthcare associated. The major causes of community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults in developed countries are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and, primarily in patients over age 50 to 60 years or those who have deficiencies in cell-mediated immunity, Listeria monocytogenes.

In a United States surveillance study between 2003 and 2007, 1083 cases of bacterial meningitis were reported in adults; S. pneumoniae was responsible for 71 percent of cases, Neisseria meningitidis for 12 percent, group B Streptococcus for 7 percent, H. influenzae for 6 percent, and Listeria monocytogenes for 4 percent.

In a 2004 review of 696 cases of bacterial meningitis in adults in the Netherlands, S. pneumoniae was responsible for 51 percent, N. meningitidis for 37 percent, and L. monocytogenes for 4 percent of cases. The remaining cases were primarily due to H. influenzae, streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and gram-negative bacilli.

The distribution of pathogens depends not only upon the age of the patient but also upon the region of the world. As an example, epidemics of meningitis due to N. meningitidis occur throughout the developing world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, but are uncommon in the United States and Europe. In African countries with high rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, the majority of meningitis cases are caused by S. pneumoniae, which has been associated with a high mortality rate.Streptococcus suis is an emerging zoonosis that causes meningitis in Asia and has been linked to exposure to pigs or pork. It is the most frequent cause of bacterial meningitis in adults in southern Vietnam. Although most cases have been sporadic, an outbreak of S. suis infection occurred in Sichuan Province, China, in 2005

Health-care associated meningitis

Meningitis may also be associated with a variety of invasive procedures or head trauma. This has often been classified as nosocomial meningitis because a different spectrum of microorganisms (ie, gram-negative bacilli and staphylococci) is more likely to be implicated than that associated with community-acquired meningitis. These patients often present with clinical symptoms during hospitalization or after hospital discharge, so the term healthcare-associated meningitis is more representative of the diverse mechanisms that can lead to this illness than nosocomial meningitis. Healthcare-associated meningitis is primarily a disease of neurosurgical patients. Two large series reported a meningitis incidence of 0.3 and 1.5 percent, respectively, after neurosurgical procedures. Specific risk factors for the development of meningitis include craniotomy, placement of ventricular or lumbar catheters, and head trauma.

The distribution of causative organisms is appreciably different in healthcare-associated meningitis compared with community-acquired meningitis. In one series,

Gram-negative bacilli accounted for 38 percent of single episodes of meningitis, and streptococci, S. aureus, and coagulase-negative staphylococci accounted for 9 percent each. In contrast, S.

pneumoniae accounted for only 5 percent of cases, L. monocytogenes for 3 percent, and N. meningitidis for 1 percent of cases. In contrast, the majority of meningitis cases that occur after

basilar skull fracture or early after otorhinologic surgery care are caused by microorganisms that colonize the nasopharynx, especially S. pneumoniae.

Other infections

Spirochetes — The two major spirochetes that need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of aseptic meningitis are Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, and Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochete that causes Lyme disease. Leptospirosis can also cause an aseptic meningitis syndrome.

Syphilis — Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, disseminates to the central nervous system during early infection. Syphilitic meningitis can present in the setting of secondary syphilis with headache, malaise, and disseminated rash.

Lyme disease — Lyme meningitis typically occurs in the late summer and early fall, the same time as the peak incidence of enteroviral meningitis. Fungal infections — The two major fungal infections that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of aseptic meningitis include cryptococcus and coccidioidomycosis.

Cryptococcal infection — Cryptococcus neoformans produces infection following inhalation through the respiratory tract. The organism disseminates hematogenously and has a propensity to localize to the CNS, particularly in patients with severe deficiencies in cell-mediated immunity.

Coccidioidal infection — Coccidioides immitis is endemic in desert regions of the southwestern United States and Central and South America. This infection has protean manifestations, and primary infection is frequently unrecognized. Meningitis is the most lethal complication of coccidioidomycosis and is therefore crucial to recognize.

Tuberculous meningitis — Patients with tuberculous meningitis frequently have protracted headache, vomiting, confusion, and varying degrees of cranial nerve signs. Mental status changes can occur, leading to coma, seizures, and at times hemiparesis. Signs of disseminated TB are of diagnostic importance, but are often absent.