Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS)

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the gradual onset of muscle weakness, especially of the pelvic and thigh muscles. Approximately 60 percent of LEMS cases are associated with a small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and the onset of LEMS symptoms often precedes the detection of the cancer. The LEMS patients with cancer tend to be older and nearly always have a long history of smoking. In cases in which there is no associated cancer, disease onset can be at any age.

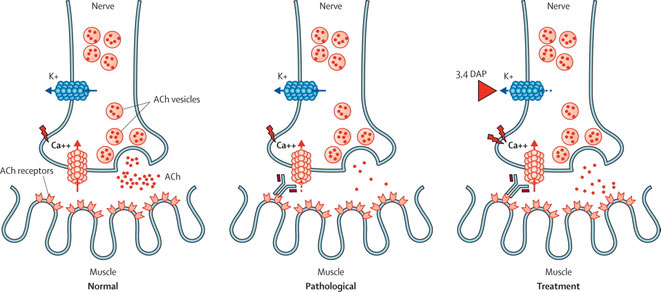

In LEMS, the characteristic muscle weakness is thought to be caused by pathogenic autoantibodies directed against voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) present on the presynaptic nerve terminal. Half of patients with LEMS have an associated tumour, small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), which also expresses functional VGCC.

LEMS is a rare disorder with a reported estimated incidence of 0.48 per million. The original description of LEMS as a disease in male patients older than 50 years is only valid for the paraneoplastic form of the disease (SCLC-LEMS). Median age at onset in this group is 60 years, and 65% of patients are men. NT-LEMS, however, is seen at all ages, with a peak age of onset of around 35 years and a second, larger peak at age 60 years. The age and sex distribution in NT-LEMS is similar to that reported for myasthenia gravis (MG), as is the genetic association with HLA-B8-DR3. This haplotype is linked to autoimmunity, and is present in around 65% of patients with NT-LEMS.

50–60% of patients with LEMS have a tumour.3 SCLC, a smoking-related lung carcinoma with neuroendocrine characteristics, is almost always the tumour type that occurs in patients with LEMS, although there have been a few reports of non-small-cell and mixed lung carcinomas.

Diagnosis of LEMS is based on clinical signs and symptoms, electrophysiological studies, and antibody testing. The clinical triad typically consists of proximal muscle weakness, autonomic features, and areflexia. Proximal leg muscle weakness is usually the first symptom noted by the patient (in 80%). Weakness of the arms is present or develops quickly. Weakness normally spreads proximally to distally, involving feet and hands, and caudally to cranially, finally reaching the oculobulbar region. Occurrence of ocular symptoms ranges from 0–80%, and bulbar symptoms from 5–80%. This wide range in prevalence is probably the result of inconsistency in the timing of assessment from presentation. Although isolated cases of purely ocular symptoms have been reported, almost all patients with ocular symptoms or respiratory failure early in the disease course also had generalised weakness. By contrast with MG, isolated weakness of the external eye muscles is rare.

Autonomic dysfunction provides another clue to diagnosis of LEMS; the type of autonomic dysfunction can be very diverse, but is usually not very debilitating. Autonomic dysfunction is found in 80–96% of patients with LEMS.

Repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) is the electrophysiological study of choice to diagnose LEMS. Single-fiber electromyography might be slightly more sensitive than RNS, but it does not distinguish between MG and LEMS and requires technical experience.

Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCC are responsible for the clinical symptoms of LEMS. These antibodies have been detected in 85–90% of patients with LEMS, and some studies report a percentage close to 100% in LEMS patients with SCLC.

Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCC are highly specific to LEMS, but have been detected in 1–4% of patients with SCLC without neurological dysfunction. Similarly, these antibodies are also found in the serum and CSF of a small number of patients with subacute cerebellar ataxia, both with and without clinical symptoms of LEMS, nearly all of whom had an associated SCLC.

10–15% of patients with LEMS have no detectable P/Q-type VGCC antibodies. The clinical phenotype of these patients is very similar to that in seropositive patients; however, the incidence of SCLC is only 12%, compared with 60–70% in seropositive patients.

All patients with LEMS, even those with a low chance of SCLC as calculated by use of the DELTA-P score, should be screened with thoracic CT and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET or an integrated FDG-PET/CT.

The first choice for symptomatic treatment of patients with LEMS is 3,4-diaminopyridine. If 3,4-diaminopyridine satisfactorily controls the symptoms of LEMS, no further treatment is needed. If symptoms remain, long-term treatment with prednisone and azathioprine should be considered.

If remission of symptoms is incomplete, prednisone might induce improvement. There are no suggestions that immunosuppressive treatment is contraindicated in patients with SCLC-LEMS.