Brachial plexus

The brachial plexus is a network of nerves formed by the anterior rami of the lower four cervical nerves and first thoracic nerve (C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1). This plexus extends from the spinal cord, through the cervicoaxillary canal in the neck, over the first rib, and into the armpit. It supplies afferent and efferent nerve fibers to the chest, shoulder, arm and hand.

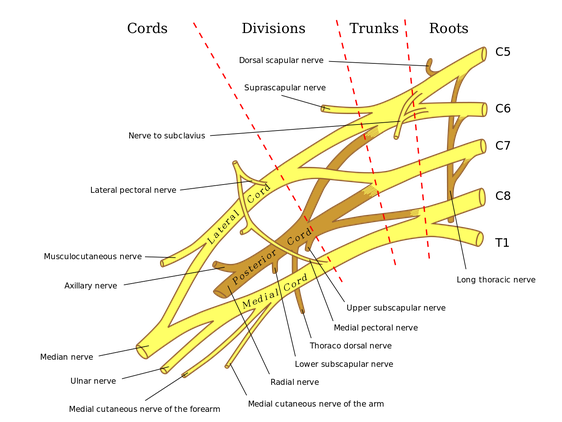

The brachial plexus is divided into five roots, three trunks, six divisions, three anterior and three posterior, three cords, and five branches. There are five "terminal" branches and numerous other "pre-terminal" or "collateral" branches, such as the subscapular nerve, the thoracodorsal nerve, and the long thoracic nerve, that leave the plexus at various points along its length. A common structure used to identify part of the brachial plexus in cadaver dissections is the M or W shape made by the musculocutaneous nerve, lateral cord, median nerve, medial cord, and ulnar nerve.

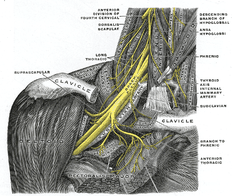

Click image to enlarge

Roots

The five roots are the five anterior rami of the spinal nerves, after they have given off their segmental supply to the muscles of the neck. The brachial plexus emerges at five different levels; C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1. C5 and C6 merge to establish the upper trunk, C7 continuously forms the middle trunk, and C8 and T1 merge to establish the lower trunk. Prefixed or postfixed formations in some cases involve C4 or T2, respectively. The dorsal scapular nerve comes from the superior trunk[2] and innervates the rhomboid muscles which retract the scapula. The subclavian nerve originates in both C5 and C6 and innervates the subclavius, a muscle that involves lifting the first ribs during respiration. The long thoracic nerve arises from C5, C6, and C7. This nerve innervates the serratus anterior, which draws the scapula laterally and is the prime mover in all forward-reaching and pushing actions.

Trunks

The roots merge to form three trunks:

- superior or upper (C5-C6)

- middle (C7)

- inferior or lower (C8, T1)

Divisions

Each trunk then splits in two, to form six divisions:

- anterior divisions of the upper, middle, and lower trunks

- posterior divisions of the upper, middle, and lower trunks

when observing the body in an anatomical position, the anterior divisions are superficial to the posterior divisions

Cords

These six divisions regroup to become the three cords or large fiber bundles. The cords are named by their position with respect to the axillary artery.

- The posterior cord is formed from the three posterior divisions of the trunks (C5-C8, T1)

- The lateral cord is formed from the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks (C5-C7)

- The medial cord is simply a continuation of the anterior division of the lower trunk (C8, T1)

The plexus ends in branches. Most branch from the cords, but a few branch directly from earlier structures. The five on the left are considered "terminal branches". These terminal branches are the musculocutaneous nerve, the axillary nerve, the radial nerve, the median nerve, and the ulnar nerve. Due to both emerging from the lateral cord the musculocutaneous nerve and the median nerve are well connected. The musculocutaneous nerve has even been shown to send a branch to the median nerve further connecting them. There have been several variations reported in the branching pattern but these are very rare.

Clinical relevance

In the simplest form, brachial plexus injuries can be classified as preganglionic or postganglionic however in clinical practice they can be mixed.

Preganglionic

injury proximal to the dorsal root ganglion therefore affecting the CNS which does not have the capacity to regenerate. (e.g. nerve root avulsion)

Postganglionic

distal to the dorsal root ganglion affecting the PNS which does have some capacity to regenerate.

(e.g. nerve ruptures and lesions in continuity)

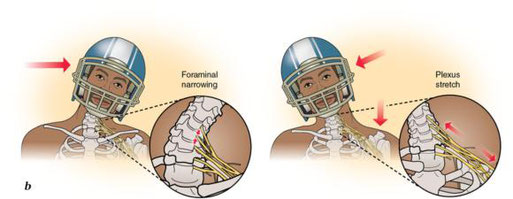

Mechanisms of injury

Brachial plexus injuries are injuries that affect the nerves that carry signals from the spine to the shoulder. This can be caused by the shoulder being pushed down and the head being pulled up, which stretches or tears the nerves. Injuries associated with malpositioning commonly affect the brachial plexus nerves, rather than other peripheral nerve groups. Due to the brachial plexus nerves being very sensitive to position, there are very limited ways of preventing such injuries. The most common victims of brachial plexus injuries consist of victims of motor vehicle accidents and newborns.

Acute brachial plexus neuritis is a neurological disorder that is characterized by the onset of severe pain in the shoulder region. Additionally, the compression of cords can cause pain radiating down the arm, numbness, paresthesia, erythema, and weakness of the hands. This kind of injury is common for people who have prolonged hyperabduction of the arm when they are performing tasks above their head

Mechanisms of injury:

- Motorcycle accidents

- Sports injuries

- Penetrating wounds

- Injury during birth

- Tumours

- Post-infectious/auto-immune (Parsonage-Turner syndrome)

Based on the location of the nerve damage, brachial plexus injuries can affect part of or the entire arm. For example, musculocutaneous nerve damage weakens elbow flexors, median nerve damage causes proximal forearm pain, and paralysis of the ulnar nerve causes weak grip and finger numbness. In some cases, these injuries can cause total and irreversible paralysis. In less severe cases, these injuries limit use of these limbs and cause pain.

The cardinal signs of brachial plexus injury are pain, weakness in the arm, diminished reflexes, and corresponding sensory deficits.

- Erb's palsy. The position of the limb, under such conditions, is characteristic: the arm hangs by the side and is rotated medially; the forearm is extended and pronated. The arm cannot be raised from the side; all power of flexion of the elbow is lost, as is also supination of the forearm.

- Klumpke's paralysis, a form of paralysis involving the muscles of the forearm and hand.

A characteristic sign is the clawed hand, due to loss of function of the ulnar nerve and the intrinsic muscles of the hand it supplies.

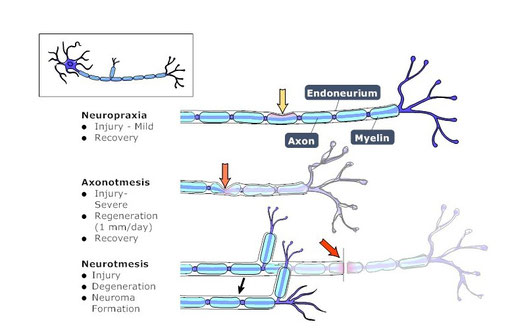

The severity of brachial plexus injury is determined by the type of nerve damage. There are several different classification systems for grading the severity of nerve and brachial plexus injuries. Most systems attempt to correlate the degree of injury with symptoms, pathology and prognosis. Seddon's classification, devised in 1943, continues to be used, and is based on three main types of nerve fiber injury, and whether there is continuity of the nerve.

Neurapraxia: The mildest form of nerve injury. It involves an interruption of the nerve conduction without loss of continuity of the axon. Recovery takes place without wallerian degeneration.

Axonotmesis: Involves axonal degeneration, with loss of the relative continuity of the axon and its covering of myelin, but preservation of the connective tissue framework of the nerve (the encapsulating tissue, the epineurium and perineurium, are preserved).

Neurotmesis: The most severe form of nerve injury, in which the nerve is completely disrupted by contusion, traction or laceration. Not only the axon, but the encapsulating connective tissue lose their continuity. The most extreme degree of neurotmesis is transsection, although most neurotmetic injuries do not produce gross loss of continuity of the nerve but rather, internal disruption of the nerve architecture sufficient to involve perineurium and endoneurium as well as axons and their covering. It requires surgery, with unpredictable recovery.

A more recent and commonly used system described by the late Sir Sydney Sunderland, divides nerve injuries into five degrees: first degree or neurapraxia, following on from Seddon, in which the insulation around the nerve called myelin is damaged but the nerve itself is spared, and second through fifth degree, which denotes increasing severity of injury. With fifth degree injuries, the nerve is completely divided.